Reproducible python environments can be tricky, especially so when your codebase requires external non-python dependencies that need to be installed outside your virtualenv. Docker is the defacto tool to solve this problem nowadays but, if your workflow requires access to specific hardware resources such as GPUs, things get a bit more complicated.

In this post I cover my approach to repeatable environments with GPU support and a minimum amount of external setup.

You can jump straight into the recipe, if you are already familiar with the problem and just need a working solution. You can also clone the recipe from its GitHub repo.

Python package management

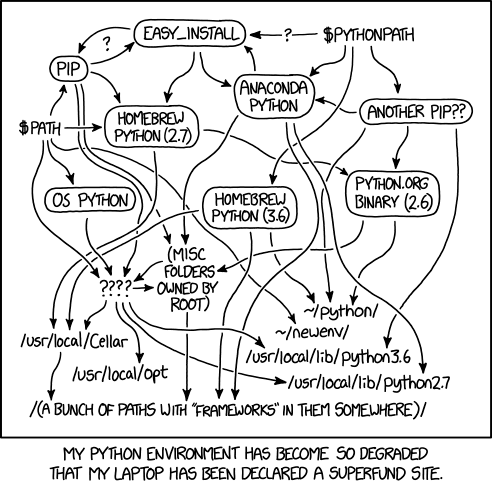

Python’s package management story is a convoluted affair compared to Rust’s Cargo or Javascript’s npm. The language was publicly released 30 years ago and the development landscape has changed much since then. There’s never been more people using it, on all kinds of projects, at all sorts of scales. This doesn’t come without drawbacks, however, and currently one of the roughest edges when developing in python revolves around package management and distribution.

If you’ve worked on multiple python projects before, you will be pretty familiar with these setup requirements to get a working dev environment:

- python interpreter with a compatible version (2 vs 3, but it’s also pretty frequent to require a specific version of 3.x)

- system wide libraries (required to build / run a python dependency)

- virtualenv containing the project’s python dependencies

Out of the three points above, you might encounter more or less based on the specifics of your project. If you are lucky and all your dependencies come packaged as a wheel, you won’t have to install any system wide library to your dev machine. Similarly, you might already be using an alternative package manager to pip, such as pipenv or poetry, which integrate virtualenvs into the package manager, along with improved dependency resolution and a more streamlined workflow 1.

For all the cases where you can’t avoid installing non-python dependencies, which is often in any non-trivial python project, the typical solution is to package your environment in a Dockerfile and work using containers directly. Setting up projects directly with docker ensures that system wide dependencies will not be missing and you can also avoid setting up a virtualenv. Still, if you need access to your GPU, by default, Docker will not let you2.

Conda to the rescue

conda is a package manager typically used for Python, but not limited to it. This means you can use it, like pip, to manage all your python dependencies and, additionally, it will also manage those pesky system-wide dependencies you needed to preinstall. In the world of deep learning, this means that each environment will have its own independent copy of the CUDA toolkit installed. conda also installs non-python dependencies inside the virtual environment. So it is perfectly possible to have multiple projects, locally, using conflicting packages and library versions. Even CUDA. Without the need to Dockerize anything.

My recommended approach, if you’re not tied to any other of the alternative package managers, is to setup projects with conda, use the conda environment to develop locally and dockerize the project for deployment in production. The amount of setup is minimal, the environment is self-contained, and it’s the easiest way to get your GPU running and test your experiments with. It’s also really easy to package into a docker image or to setup in environments with limited permissions. For example, I’ve executed training scripts on my university’s HPC with this conda setup without having to limit myself to the installed versions of its software libraries.

The Recipe

1. Install nvidia graphic drivers

This is the only step for which you will need root permissions to your system. For this recipe I am using Ubuntu 20.04 LTS. The steps should be the same for any supported Ubuntu image. If you are using any other Linux distribution, Google is your friend. Should be pretty easy regardless.

First, we make sure that the ubuntu-drivers utility is installed in our system:

$ sudo apt update && sudo apt install -y ubuntu-drivers-common

We check that the utility detects our GPU correctly:

$ sudo ubuntu-drivers devices

== /sys/devices/pci0000:00/0000:00:04.0 ==

modalias : pci:v000010DEd0000102Dsv000010DEsd0000106Cbc03sc02i00

vendor : NVIDIA Corporation

model : GK210GL [Tesla K80]

driver : nvidia-driver-450-server - distro non-free

driver : nvidia-driver-418-server - distro non-free

driver : nvidia-driver-450 - distro non-free

driver : nvidia-driver-460-server - distro non-free

driver : nvidia-driver-460 - distro non-free recommended

driver : nvidia-driver-390 - distro non-free

driver : xserver-xorg-video-nouveau - distro free builtin

And proceed to install the drivers:

$ sudo ubuntu-drivers autoinstall

This command will automatically choose the version, but you can also run $sudo apt install nvidia-driver-<version> with any of the drivers listed by ubuntu-drivers, if you have some specific requirements. After that, reboot your machine for the changes to take effect. Once that’s done, run nvidia-smi to check that your GPU appears properly listed:

$ nvidia-smi

Fri May 7 10:28:05 2021

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| NVIDIA-SMI 460.73.01 Driver Version: 460.73.01 CUDA Version: 11.2 |

|-------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

| GPU Name Persistence-M| Bus-Id Disp.A | Volatile Uncorr. ECC |

| Fan Temp Perf Pwr:Usage/Cap| Memory-Usage | GPU-Util Compute M. |

| | | MIG M. |

|===============================+======================+======================|

| 0 Tesla K80 Off | 00000000:00:04.0 Off | 0 |

| N/A 71C P8 36W / 149W | 13MiB / 11441MiB | 0% Default |

| | | N/A |

+-------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| Processes: |

| GPU GI CI PID Type Process name GPU Memory |

| ID ID Usage |

|=============================================================================|

| 0 N/A N/A 928 G /usr/lib/xorg/Xorg 8MiB |

| 0 N/A N/A 976 G /usr/bin/gnome-shell 3MiB |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

And that’s all! Onto conda next.

2. Install miniconda

miniconda is a minimal distribution of conda, with everything you need to get started without any of the bloat. To install miniconda locally run:

$ curl https://repo.anaconda.com/miniconda/Miniconda3-latest-Linux-x86_64.sh -o miniconda.sh \

&& bash miniconda.sh -b \

&& rm miniconda.sh

This will download and install everything you need on the local folder $HOME/miniconda3. To finish your setup, run conda init with your shell of choice. bash in this case:

$ $HOME/miniconda3/bin/conda init bash

This will modify your PATH so you will have the conda command available and also allow you to activate and deactivate environments easily. Make sure you open a new shell for the changes to take effect.

3. Manage your conda environment

Now that we have everything setup, let’s create a new environment for our deep learning project. When we create an environment we can also specify which python version we want to use. python 3.8 in this case:

(base): $ conda create -y -n new-dl-project python=3.8

If we activate the environment, any of the subsequent installs or scripts will be executed against it, without affecting the global environment:

(base): $ conda activate new-dl-project

(new-dl-project): $ which python

/home/octavi/miniconda3/envs/new-dl-project/bin/python

(new-dl-project): $ python --version

Python 3.8.8

To install pytorch we will run:

(new-dl-project): $ conda install -y pytorch torchvision torchaudio cudatoolkit=10.2 -c pytorch

If we take a closer look at the command, we can see how conda manages the installation of the necessary cuda toolkit libraries in the environment itself (we could be running something else in our system). We are also specifying an alternative installation channel, as per the pytorch docs. When using conda, if you don’t find the package you are finding in the default channel, you can try searching it in channels managed by other maintainers. If that also fails, you can default to pip. It will still install those packages on the project’s environment.

Once the installation finishes, we can finally test running pytorch and checking for CUDA support:

(new-dl-project): $ python -c 'import torch; print(f"{torch.cuda.is_available()=}")'

torch.cuda.is_available()=True

Finally, we should export the environment definition to allow other teammates (and ourselves) to replicate it in the future. To do this, conda offers multiple options. If we want to get a carbon copy of every installed dependency, plus build version, we can run:

$ conda env export

This list is convenient to ensure a 100% reproducible build, but it is not cross compatible. Many of the builds are platform dependent and if that is the only thing you commit to your repo you might find it impossible to install the same dependencies on another OS or PC even.

A less strict option is to list all installed packages with version, without build. This is very similar to running pip freeze and I would recommend to add that to your repo, as follows:

(new-dl-project): $ cd <some-path>/new-dl-project

(new-dl-project): $ conda env export --no-build > environment.yml.lock

As with pip freeze this lists all installed packages in the environment, whether they are direct or indirect dependencies of the project. This is not ideal from a maintenance point of view and makes library updates harder to perform.

My personal recommendation is to save an environment.yml with just the installs we have explicitly performed:

(new-dl-project): $ cd <some-path>/new-dl-project

(new-dl-project): $ conda env export --from-history > environment.yml

This generates a YAML file, environment.yml with only the dependencies from the conda install command:

(new-dl-project): $ cat environment.yml

name: new-dl-project

channels:

- default

dependencies:

- python=3.8

- torchaudio

- pytorch

- cudatoolkit=10.2

- torchvision

prefix: /home/octavi/miniconda3/envs/new-dl-project

This version of the command does NOT specify the library version unless we have explicitly set it while installing the package. Since this is not ideal either, what I do, is to edit this file manualy with the version numbers of environment.yml.lock that I’ve created beforehand. It is also very important that you add any missing channel that may appear in environment.yml.lock. Additionally, I remove the prefix line, since it is optional and will depend on the local config. Less spurious changes to be commited to the repo this way:

To finish this conda tutorial, let’s try destroying the environment we have just created and recreating it from the environment.yml file we have prepared:

# Destroy the environment

(new-dl-project): $ conda deactivate

(base): $ conda env remove -n new-dl-project

# Check that the environment no longer exists

(base) octavi@instance-1:~/new-dl-project$ conda env list

# conda environments:

#

base * /home/octavi/miniconda3

# Recreate it from environment.yml

(base): $ conda env create -f environment.yml

# Check that pytorch runs

(base): $ conda activate new-dl-project

(new-dl-project): $ python -c 'import torch; print(f"{torch.cuda.is_available()=}")'

torch.cuda.is_available()=True

Add environment.yml and environment.yml.lock to your git repo and you should be ready to go. Just remember to update both files whenever you add or update a new dependency via conda install, conda update or similar. Also remember to add the version numbers and channels to your environment.yml.

4. Dockerize project

So far, we have setup a reproducible development environment that allow us to run our project on bare metal, without the need of superuser permissions nor the necessity to perform any global installs. Everything is self-contained.

Still, even though this setup is very convenient to develop in, it may not be appropriate to deploy our project to production. This part of the recipe will cover how to package our conda environment inside a docker image.

First, we will create a basic Dockerfile in our project’s folder:

For demo purposes, we will also create a very basic docker-compose.yml configuration:

You can build that with the typical docker-compose build, and run the service with docker-compose up. It should return something like this:

(base): $ docker-compose up

Recreating new-dl-project_example_1 ... done

Attaching to new-dl-project_example_1

example_1 | torch.cuda.is_available()=False

new-dl-project_example_1 exited with code 0

As you might have noticed, running our example through docker results in CUDA not being available. This is because, by default, docker does not expose resources such as GPUs to the container, so they can’t be used while running from it. Still, since in production we are usually only evaluating models (not training them) doing so on CPU can be reasonable.

In the Dockerfile I’ve separated the section per blocks. Essentially putting together all the steps of this recipe. I’ve also added a few commands to ensure that packages will be purged and not stored in the docker image, to save some space. If we wanted a more elaborate setup, with the possibility to be used via devcontainers or similar in VSCode, I would setup a non-root user with a configurable UID. This way it would be possible to mount the project as a volume and run it through the container with the same permissions as our local user. Regardless, this basic setup should be most of what you need to dockerize any similar conda environment.

Summary

I’ve collected this recipe on its own GitHub repo to make it easier to share and modify.

In this post we’ve seen some of the reasons why python packaging is difficult, especially when our projects have non-python dependencies. This is the case of deep learning projects, that depend on the CUDA toolkit to train new models.

I’ve presented an approach to managing python environments with conda that allow any user to install a fully working environment in isolation without the need of any extra user permissions. This approach works well to develop locally and it is easy to dockerize for deployment in production. I’ve also detailed my particular approach at keeping track of dependencies on environment.yml, to facilitate reproducible environments which are easy to upgrade and not clash with other projects you might have to work in parallel.

In future parts of this series I’ll detail how we can configure docker to run GPU tasks, as well as ways to configure environments with package managers other than conda. The following posts will be handy for those of you that need to dockerize legacy projects or have hard constraints on your package manager of choice.

-

Historically

pipdependency resolver has been pretty limited and is known to let the user install mutually incompatible versions of a dependency. pip v20.3 onwards offers improvements on the resolver, although projects such as pipenv or poetry have much stricter consistency goals. The whole topic is worth another series of posts in itself. Apart from the dependency resolution, tools like poetry also integrate the virtualenv workflow similar to whatnpmdoes with its ability to configure project scripts. ↩︎ -

It is possible to setup Docker and docker-compose with GPU support with nvidia-container-runtime. I’ll detail its usage in future posts of this series. ↩︎