Another short post on pybind11 and how you can leverage its call guard directives to release the GIL and achieve true multithreaded parallellism in python.

It’s no secret to anyone developing in python that running CPU-bound tasks in a multithreaded pool will result in no speedup due to the existence of the GIL. The GIL has been source to many endless debates and attempts at improved performance. There are even some very recent developments that may finally lead to its demise, but that day lies in a very uncertain future still. Typical approaches to concurrency in python are asyncio and threads for IO bound tasks, while multiprocessing and C-extensions are the preferred approach for CPU-bound tasks. For the purposes of this blogpost, we will center ourselves around the latter.

The GIL is used by the python interpreter for referebce counting around PyObjects. So it is possible to build C-extensions that release it, as long as they don’t interact with any python code during its execution. For the purposes of this post, I’ve setup an sample project on github, with a very simple C++ pybind11 extension. To simulate a cpu bound task, I’ve implemented a very naive fibonacci sequence function, both in python and C++.

python version

def py_fib(n):

if n < 2:

return 1

return py_fib(n-2) + py_fib(n-1)

C++ version

#include <pybind11/pybind11.h>

#define STRINGIFY(x) #x

#define MACRO_STRINGIFY(x) STRINGIFY(x)

long fib(long n) {

if (n < 2) {

return 1;

}

return fib(n-2) + fib(n-1);

}

namespace py = pybind11;

PYBIND11_MODULE(pybind11_extension, m) {

m.doc() = R"pbdoc(

Pybind11 example plugin

-----------------------

.. currentmodule:: pybind11_extension

.. autosummary::

:toctree: _generate

)pbdoc";

m.def("cpp_fib", &fib, R"pbdoc(

Give fibonnacci sequence value for a given number.

)pbdoc");

m.def("cpp_fib_nogil", &fib, py::call_guard<py::gil_scoped_release>(), R"pbdoc(

Give fibonnacci sequence value for a given number.

)pbdoc");

}

The only interesting bit on this excerpt would be the definitions of the binding themselves. Using the PYBIND11_MODULE syntax, we create the python module, specify its functions, and how they are linked back into C++. If we do that, pybind11 will take care of the type conversion back and forth between layers.

Another important thing is the possibility to specify that a function call WILL release the GIL. We don’t even need to touch the implementation of the function itself. We can just pass a directive during the module definition:

m.def("cpp_fib_nogil", &fib, py::call_guard<py::gil_scoped_release>(), R"pbdoc(

Give fibonnacci sequence value for a given number.

)pbdoc");

If you need a more detailed explanation around it, I would suggest checking out the documentation.

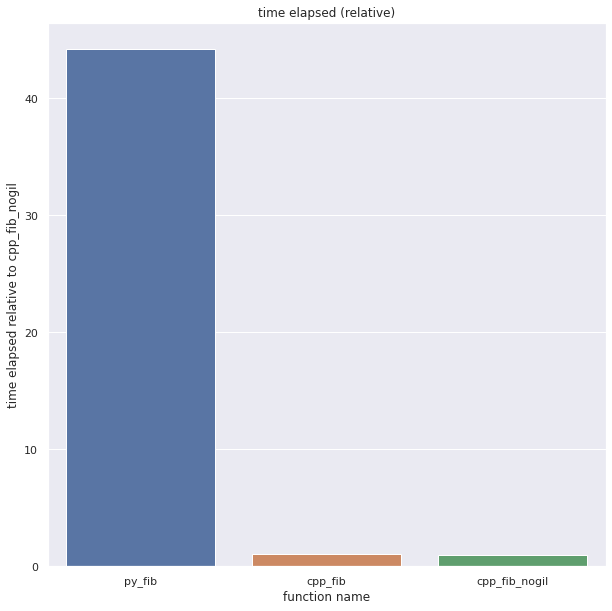

So, if we run a benchmark of the 3 functions, single threaded, we get this:

So far, no surprises. For the same inputs, The C++ version is over 40 times faster. Still, GIL or no GIL, both C++ exposed functions perform the same on a single threaded workload.

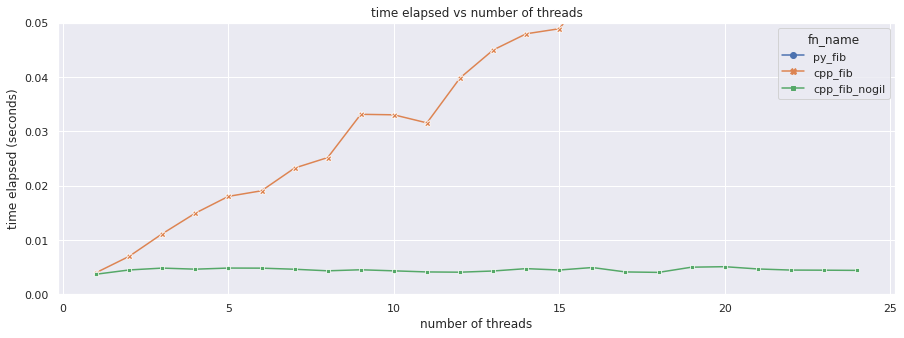

Now, what would happen if we use a concurrent.futures.ThreadPoolExecutor to call both cpp_fib and cpp_fib_nogil? Will we see a linear increase in time spent? Or can we really execute code in parallel?

The test executed the same function on 24 threads, on a CPU with 24 logical cores, so you would expect a flat line if it was truly parallel. And yes, as we can see, cpp_fib_nogil actually lives up to that expectation. Similarly, even though cpp_fib is a C++ call, since it does NOT release the GIL, there’s a linear increase in time elapsed, as tasks are completed sequentially. py_fib performs so badly by comparison that the line is off the charts.

I prepared a script in the repo itself in case you want to run the test yourselves. Or a notebook with the graphs.

Now, I will admit, this is a very contrived example. Unfortunately, things will not be so clear cut in the real world. A serious challenge tends to be that, to perform whatever operation you want to optimize, you need access to the state of the program. And that usually means that your C++ extension needs awareness on the content of many python objects. That leaves you with 2 alternatives:

- Accessing the python objects from C++, with slower access and binding yourself to the GIL

- Transform the python objects to a pure C++ representation, paying the memory and transformation overhead

Neither option is great, but if your workload loops on mostly the same data, you can organize your C extension to pay the overhead just once, during initialization, whereas the whole loop can be in pure C++. Going back to our tortured fibonacci example, we could implement something like so:

#include <vector>

#include <pybind11/pybind11.h>

#include <pybind11/stl.h>

#define STRINGIFY(x) #x

#define MACRO_STRINGIFY(x) STRINGIFY(x)

long fib(long n) {

if (n < 2) {

return 1;

}

return fib(n-2) + fib(n-1);

}

class FibHolder {

public:

FibHolder(const std::vector<int> &fib_values)

: fib_shit(fib_values) {}

static FibHolder create(const std::vector<int> &fib_shit) {

return FibHolder(fib_shit);

}

long do_fib(int idx) {

return fib(fib_shit.at(idx));

}

private:

std::vector<int> fib_shit;

};

namespace py = pybind11;

PYBIND11_MODULE(pybind11_extension, m) {

m.doc() = R"pbdoc(

Pybind11 example plugin

-----------------------

.. currentmodule:: pybind11_extension

.. autosummary::

:toctree: _generate

)pbdoc";

py::class_<FibHolder> fib_holder(m, "FibHolder", R"pbdoc(

Class that will serialize context to C++, so you can run C++ functions on it later.

)pbdoc");

fib_holder

.def(py::init<>(&FibHolder::create))

.def("do_fib", &FibHolder::do_fib)

.def("do_fib_nogil", &FibHolder::do_fib, py::call_guard<py::gil_scoped_release>());

}

We have created a new class, FibHolder, which takes a List[int] in the constructor, and transforms it into a native std::vector<int>. That would be the initialization cost. Finally, we call FibHolder.do_fib(idx), passing only the index on the vector. This could be called from python like so:

import concurrent.futures

from pybind11_extension import FibHolder

num_threads = 10

fib_values = [30] * num_threads

fh = FibHolder(fib_values)

with concurrent.futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=num_threads) as executor:

executor.map(fb.do_fib_nogil, range(num_threads))

Again, the example is contrived, but the concept powerful. If you are in dire need of real performance, this allows you to pay the serialization cost just once, and then parallellize the execution of the calculations.

The repo contains all of the referenced code in this post. Hope you’ve enjoyed it, and happy coding!